600 Million Years of Cynon Valley

Geological History

2. The earliest times: the history of the rocks deep below the Cynon Valley

2.1 The Pre-cambrian

If a resident of the Cynon Valley could travel back in time some 600 million years, to late Pre-cambrian times, and stand on those rocks that now lie at a depth of some 3 kilometres below the valley floor, that person would be standing near the corner of a very cold barren continent which extended below what is now the English Midlands and possibly to southern Scandinavia but its limits in that direction are conjectural. The known extent of the continent indicates that it was not large and was what geologists call a micro-continent and has been named Avalonia.

In the direction of what is now the northwest, the resident would see a shallow continental shelf sea and beyond it an ocean where mid and north Wales are now. The limit of the continental crust would have been from what is now mid Pembrokeshire along the Gwendraeth Valley, through mid Wales to the east of Builth Wells and continue through Shropshire west of the Longmynd. A major fracture in the crust now exists along this line, named the Llandyfaelog - Carreg Cennen Disturbance in South Wales and the Pontesford - Linley fault in Shropshire. Two other major faults, one along the Swansea Valley and another along the Vale of Neath, also originated in relation to this continental margin. These are complex structures composed of several fracture planes which coalesce in some places along their length and in other places split into several branches. Repeated movements of differing nature along those three faults at different times, in response to differing stress conditions, influenced much of the evolution of the crust in south Wales and the Borderland. The Vale of Neath Fault can be traced from Neath across Moel Penderyn (Figure 2) north-eastwards along Cwm Cadlan, past Crughywel to where the River Monnow with its Black Mountain tributaries are deflected along it between Pandy and Pontrilas. The earth tremor resulting from the latest of these movements was felt by people throughout South Wales at midnight on 28th February 2023 and several recordings of the location of the epicentre (position on the surface above the focus of the movement at depth) from the Vale of Neath to Llangenny, east of Crughywel, are on the exact line of this structure.

Figure 2. Moel Penderyn from Cwm Cadlan showing the line of the Dinas Fault (a branch of the Vale of Neath Disturbance)

along the black scar to the right of the summit.

2.1.1 Avalonia

The nature of that basal continental crust has not been determined in detail below the cover rocks of the South Wales Coalfield but assumptions as to its nature can be inferred from rocks of a comparable age in the Malvern Hills and along the Church Stretton Valley in Shropshire. Such comparisons indicate that much of it is composed of volcanic rock as seen in Pembrokeshire but, south of Carmarthen, sedimentary rocks of the same age with fossils occur, thus indicating that the oldest continental rocks of this area are varied. Rocks with the same kind of fossil are well known in the rocks of Charnwood Forest, Leicestershire, which does indicate a relationship between those two areas and, by inference, those below the Cynon Valley also. This ancient continent is far from being amongst some of the earliest land masses since studies on the ages of its rocks indicate that it is less than 800 million years old. Avalonia itself is regarded as a fragment resulting from the break-up of an earlier single large supercontinent called Rhodinia that itself formed by all the continents that existed at that time coalescing, 1100 million years ago. If that time-travelling resident of the valley was on Avalonia at night 600 million years ago he or she would note that the sky was unfamiliar because the landmass at that time was situated about 80 degrees south of the equator and the sky would have been that seen in the southern hemisphere. (Figure 3)

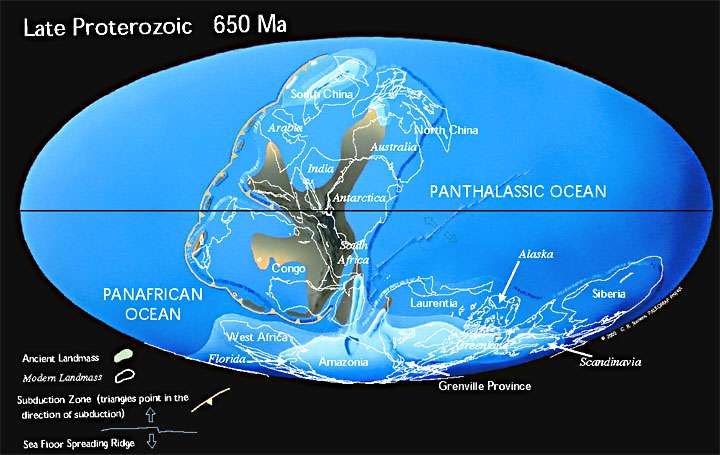

Figure 3. This map illustrates the break-up of the supercontinent, Rhodinia, which formed

1100 million years ago. The Late Pre-cambrian was an “Ice House” world, much like the

present day. The microcontinent of Avalonia, not named on the map, is situated towards the

bottom right at the western extremity of the ancient land mass indicated as Scandinavia.

Note that the outline of present day continents or fragments of continents

is also indicated

on the map.

2.2 Avalonia during the Cambrian, Ordovician and Silurian Period.

Since the area now occupied by the Cynon Valley was on a stable continental crust the overall seismic conditions were calm and there is no evidence, not even from analogous nearby areas, that it was submerged during the Cambrian and Ordovician periods and in all likelihood it was a flat low lying land area. However, a very different set of conditions existed to the west. There during the Cambrian and Lower Ordovician periods, sedimentary deposits thousands of metres thick were accumulating and, because the underlying oceanic crust was gradually being dragged south eastwards below the continent, many earthquakes and tremors would have occurred. The position of Avalonia, partly submerged by a shallow sea and partly land right against a major subduction zone can be seen on Scotese's map of the Late Cambrian world (Figure 4).

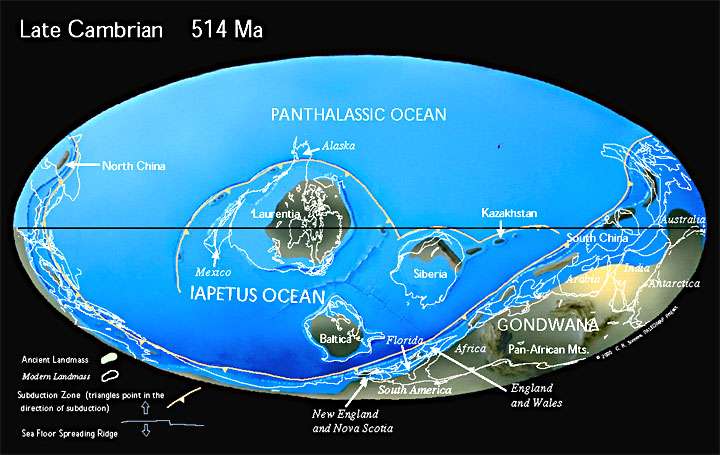

Figure 4. The Late Cambrian World. (http://www.scotese.com/newpage12.htm).

The very fine grained mud deposited along the deep water trench associated with the major subduction zone to the northwest of Avalonia, in that part of the basin that would become Gwynedd, eventually developed into the well known Welsh Slate that provided roofing material for most of the older buildings in the Cynon Valley. This process, of course, would not really be noted by our time traveller but later that individual would have felt the shocks of earthquakes, seen ash clouds and fiery skies to the northwest during the formation of a large chain of volcanoes in an island arc similar to that of present day Indonesia during the late Ordovician (440 Ma). The rocks produced by these volcanoes exist today as the high ground of Cader Idris and Eryri with some as far east as the Berwyn Hills and parts of south Shropshire. The position of Avalonia in its island arc environment similar to present day Indonesia can be seen on Scotese’s Middle Ordovician map (Figure 5).

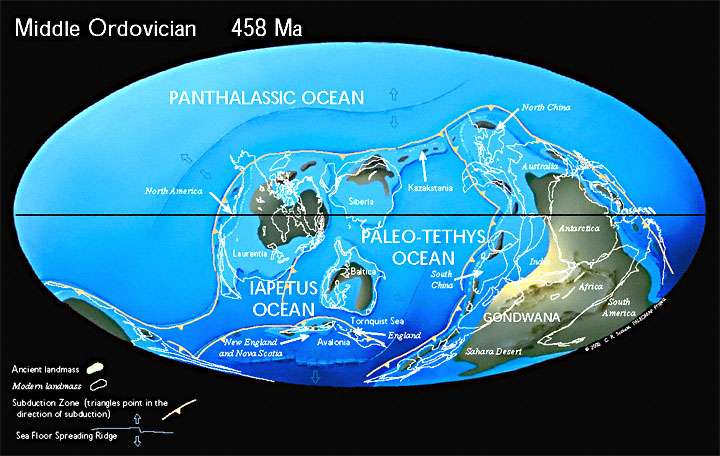

Figure 5. The Middle Ordovician World. (http://www.scotese.com/newpage1.htm).

All of this was the result of the Iapetus Ocean (indicated on the maps) closing as Avalonia gradually moved towards the continental mass of Laurentia, that is now north eastern Canada and Greenland. By Silurian times (Figure 6) the Iapetus Ocean basin was much smaller and deep water sediment was filling the area that would become mid-Wales. The shelf sea to the south, however, advanced and retreated across Avalonia and these changes can be inferred for rocks below the Cynon Valley from rocks in the Welsh Borderland and in the area between Usk and Pont-y-Pŵl where they are exposed. The nature of the sediments deposited at that time depended on the position of the shoreline and, in general, sandstones, mudstones and shales were formed when sediment was transported into the area but towards the top of the succession limestones, some with reef fossils, occur, indicating that there were periods when the sea was clear and the climate was tropical because by the mid Silurian (425Ma) Avalonia had travelled as far north as the tropics.

Figure 6. The middle Silurian world. Note that Avalonia is now almost completely joined with Laurentia and

also that a new ocean, the Rheic Ocean which will later play an important part in the development of the

Cynon Valley, has developed to the south east. http://www.scotese.com/newpage2.htm

2.3 The Devonian Period

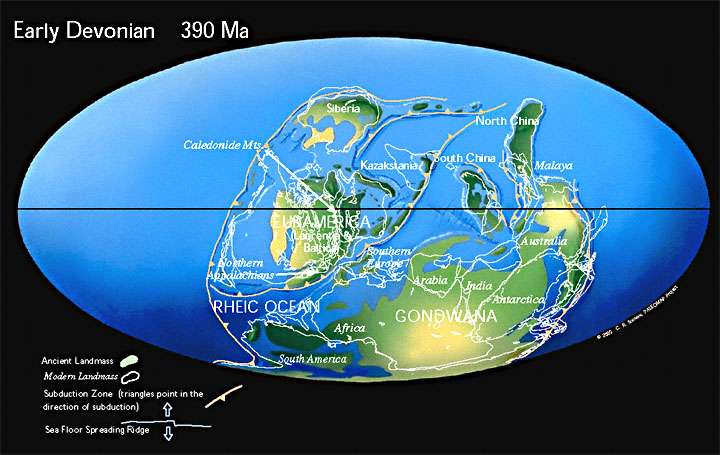

By late Silurian and early Devonian times the process of closure of the ocean was almost complete and a high mountain chain, extending from what are now the Appalachian Mountains in the eastern US and Canada to eastern Greenland and northern Scandinavia including highland Britain, had formed and the location of the Cynon Valley now existed in an entirely different environment. That mountain chain is referred to by geologists as the Caledonides, from the Roman name for Scotland where much of the pioneering studies of those rocks were undertaken. The Lower Devonian map (Figure 7) indicates the situation before the final closure of the Iapetus Ocean, which was Mid-Devonian and hence the mountain chain has not fully formed. By the end of the Devonian period the continents of Europe and America had joined.

Figure 7. The Early Devonian world. On the map Avalonia is at the southern part of Euramerica.

Our time traveller would certainly see part of the new mountain chain that had developed to the northwest and would now be standing on arid and largely barren coastal flats with large rivers, originating in the mountains, flowing across them rather like the present day Colorado delta and covering the now buried ancient continent of Avalonia (Figure 8). The night sky would still be a southern sky but the climate was hot and dry because the land was now 30 degrees south of the equator.

Figure 8. An impression of the Lower Devonian in the location of the Cynon Valley. The view

depicts low lying coastal arid plains with large meandering rivers and with the mountain

chain of mid and north Wales in the distance.

The rocks formed during the Devonian now lie deep below the Cynon Valley

but their nature can be inferred with confidence from rocks of the same

age on the Bannau Brecheiniog, the Black Mountains, the undulating lands

of Monmouthshire and Herefordshire and in a narrow strip as far west as

the Pembrokeshire coast near St. Brides. Erosion of the mountain chain

and river transport of the debris gave rise to more than a kilometre thickness

of red-brown mudstones and sandstones, known as the Old Red Sandstone,

as can be seen today in the Bannau Brecheiniog and the Black Mountains.

A bore hole drilled through the Coalfield near Maesteg revealed a succession

of about a kilometre of Old Red Sandstone with the same basal sandstone

as occurs near Usk indicating that the presence of these beds below the

Cynon Valley is highly likely. The Devonian period also saw the first appearance

of primitive land plants, Thalomia breconensis, named after the

location where it was first identified near Storey Arms. These conditions

persisted for about 50 million years with the rivers flowing into a developing

large ocean to the south, called the Rheic ocean (shown on the Silurian

and Devonian maps), with the land margin in a variable position more or

less across what is today north Somerset.

Cynon Valley History Society is a Registered Charity. Charity No. 510143.

All information © Cynon Valley History Society